Joey Fauerso’s work is part of hemisfair’s new garden

Children visiting HemisFair Park this summer will have a whole new playground to explore and enjoy. Created by six San Antonio artists and appropriately named PLAY, this playground will consist of six separate areas within the enhanced green space of the park, dubbed the Yanaguana Garden. Both the garden and the play stations are part of the overall HemisFair redevelopment plan adopted by the city council in 2011.

Artist Joey Fauerso was “very excited” to have been asked to participate in the project. The mother of two little boys who played in the old HemisFair Park, she had no trouble devising a fun space for kids. “I was thinking of all the things they would like,” says Fauerso, a prominent contemporary painter and video artist. “I came up with the idea of a child-size campsite with tent structures in a semi-circle surrounded by a grove of trees. All plans had to be approved by Public Art San Antonio, so there were a few slight changes, but the core idea stayed the same. I think it will be a place that sparks the imagination and creativity for kids, but I also wanted it to have artistic integrity.”

She shows me her drawings of the campsite since the actual structures have not yet been manufactured. Each tent will be made of powder-coated steel in a range of graduated hues of blue to reference the sky, and once installed, will be lit up from inside by low-voltage LED lights at night. In addition to encouraging make-believe play, the campsite would “point to the presence of natural habitats and experiences in an urban landscape,” to quote her artist statement.

It so happened that while she was experimenting with a cardboard version of a tent one day in the park, a school group came by, and the kids immediately wanted to go inside. “I felt – OK, I think it’s going to be magical for kids,” says the artist.

We are having this conversation in mid-May in her south side home, a former restaurant building that she and her sculptor husband, Riley Robinson, have beautifully adapted and renovated into a spacious, light-filled house. Art by other well-known San Antonio artists is everywhere: Hills Snyder, Ethel Shipton, Ken Little, Cathy Cunningham and others. The couple’s studios are just across a narrow passageway from the house, and there’s a studio within the studio for their sons Brendan, 6, and Paul,3. Two other artist couples have bought property on the same street, she notes. It may be the beginning of a new community.

The HemisFair installation is Fauerso’s second public art undertaking. Her first was also a kid-centered project for which she redesigned the children’s reading room at the New Braunfels Public Library. These projects represent a big departure from the rest of her work. Though she started as a more or less traditional painter, during a 2005 residency in the Roswell (New Mexico) Artist in Residence Program, she developed an interest in animation, which she has cultivated ever since. A good example of her process was seen in the 2014 Artpace exhibit Invasive Species: Landscapes. Fauerso was one of three artists invited to reinterpret the idea of landscape. Her contribution was the result of a labor-intensive process that started with a video of an actual river landscape. She then painted a large number of scenes from video stills and proceeded to scan and print them on an ink jet printer. These now modified, almost abstract images were both displayed on the gallery wall and reanimated as a 55-minute video. “The idea was to expose the same thing both spatially and temporally,” explains the artist. According to a reviewer, it was also a comment on the artistic process of observation and interpretation using both old and new tools.

She Explores Different Genres

Though born in San Antonio, Fauerso grew up mostly in Fairfield, Iowa, in a transcendental meditation community her parents, Paul and Josie Fauerso, had chosen to live in. In school, the kids studied yoga and Sanskrit in addition to regular subjects. Meditation was a daily practice. “It was a rather idyllic way to grow up,” she says. “Meditation is a good way to manage stress, but also, when you get into that state beyond thoughts, it’s a very abstract experience. I feel it creates a psychic environment where you are more likely to be creative.”

She left to attend college and later pursue graduate studies in art, eventually moving back to San Antonio in 2001 with two of her school friends. Together, they opened The Bower gallery that focused on Texas artists. By the time Fauerso met Robinson (at an art opening), as well as others in the art community, she knew she wanted to stay here. San Antonio’s sense of its own history and the current momentum toward both preservation and revitalization, especially in the downtown area, are inspiring to her. Both her career and personal life have prospered ever since.

The artist’s résumé lists pages of group and solo exhibits in U.S. and European cities, from Los Angeles to Amsterdam, as well as multiple residencies, grants and awards. She’s an associate professor of art at Texas State University and is currently involved in the Open Sessions exhibition and curatorial program sponsored by the Drawing Center in New York City. At least two new shows are planned for 2016. And she’s only 38.

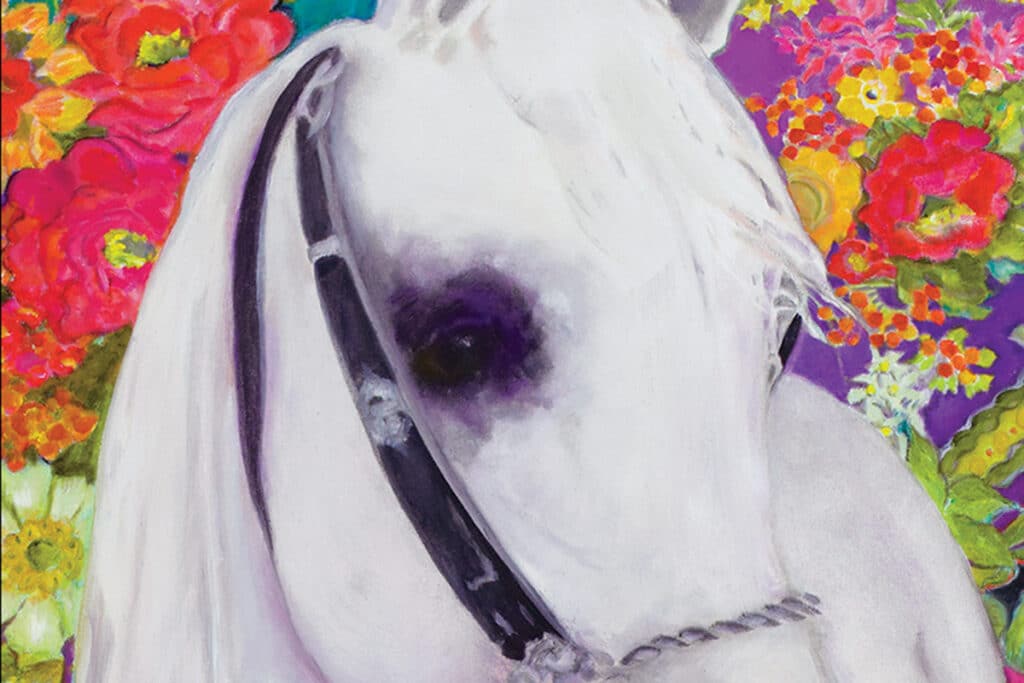

Despite her interest in video art, Fauerso points out that she has not forsaken traditional painting, though her painted images hardly look traditional. “One of the things I love about art is that it takes familiar experiences and presents them in a new way. It feels fresh, like everything is possible,” says the artist, describing essentially her own approach to art-making. Our cultural expectations about nature, the human body and gender are often blurred or upended in her paintings.

Come fall, she will be on sabbatical from teaching, which will allow her to work on a new, longer animation project based on photos her parents shot during their time in Iowa. At this point, that project is not yet defined. Quoting another artist, she explains: “I don’t start with an idea. I start with a direction. Then the work just kind of creates itself.”

Public art, however, demands a different frame of mind given that the artist is interpreting a communal rather than a strictly personal vision. For Fauerso, that’s a welcome challenge. “I would definitely like to do other public projects,” she says. “So much of what we see in the public sphere is just utilitarian, about function. Public art speaks to the less obvious qualities of human experience; it’s more about feeling than function. It presents questions, surprises and experiences that are less prescribed.”